Symbolism in Architecture is a term which is thrown around very loosely. From the classic understanding of the minaret as a marker, to the use of courtyards as enhancers of social interaction, these architectural gestures are often bannered as symbols. There is no contention on these, for obvious reasons, but the global discourse on signs, symbols and iconography has travelled a long distance. If we argue that cities are a representation of society, then the urban landscape is the sign system, making all architecture a symbol. Thus, it can be said that symbolism in today’s world goes beyond religious and cultural semantics.

There is a move towards the development of urban semiotics, the study of how symbols come about in society and how they communicate. Urban semiotics explores cultural signs, patterns of life, practicing trends, design and so on. These are the characteristics of society that evolve overtime and vary from culture to culture. Hence, symbols also develop over time and signify the concerns of the society at large.

Consider this; today, much of the debate in Architecture is over sustainable design. With depleting resources, changing climate and general rise in awareness, the idea of sustainable Architecture has gathered its due share of supporters. Albert Einstein once said, “We cannot solve problems by using the same kind of thinking we used when we created them”. Buildings coming up today tend to be conscious of their effect on the environment. It has always been the responsibility of design to provide a formal solution to a strategic problem. Now, this “conscience” is been tapped. Sustainability has become the insignia of Architecture, a symbol of the Post-Apocalyptic world – man’s last attempt to prevent extinction.

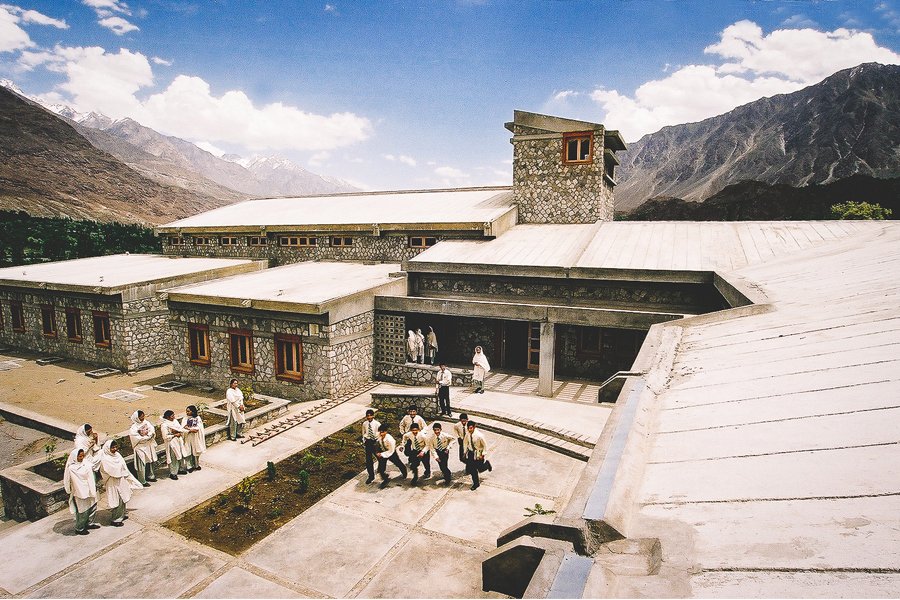

The design of Aga Khan Gahkuch, Gilgit is an effort by The Architects towards the use of green science in building design. This school aims to live up to its role of educating, not just as an institution but also as a design. The project was completed in 2004 within a span of 15 months, dating back to a time when green technology was still a relatively new idea in Pakistan. The design is case sensitive in trying to amalgamate relevant building technologies to the lifestyle of the local inhabitants. This is the very crux of sustainable design; enabling people to realize their potential to improve the quality of life and also simultaneously protect the eco system. The school complex, in essence, is geared towards establishing itself as an icon in the rugged landscape of Gilgit. It is an example of how urban pragmatics work: signs and their effect on people.

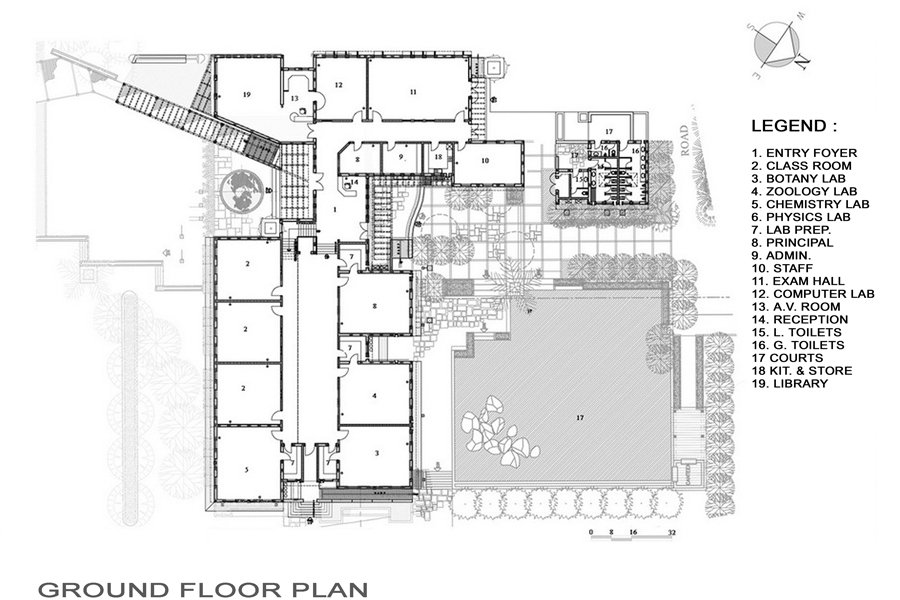

Located on a two hour drive away from the main city, this higher secondary school uses passive systems to maintain a comfortable environment throughout the varying climatic conditions. A variety of green building techniques have been employed here. Each of these represents a tradition either already practised in the region or that was once in practice. These symbols suggest a move in the right direction, a move for the betterment of the people. Roof trellises and vertical trellises covered with deciduous vines help block direct sunlight thus reducing heat gain, a technique already common in the area. Reinvention is at the very core of symbolism. A special green house window has been conceived for the school which has flaps open at the top and bottom, allowing hot air to vent by the simple rule of convection.

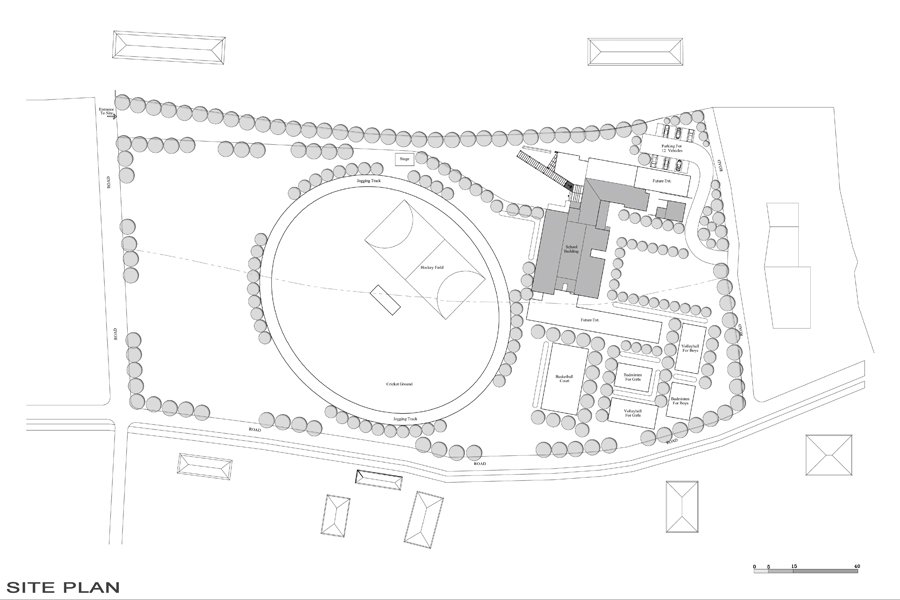

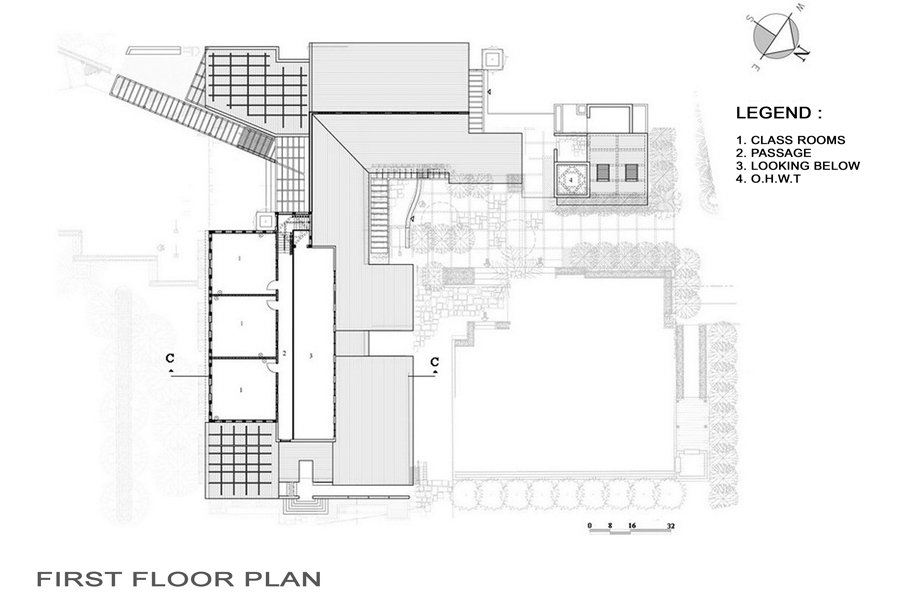

As for the plan of the school, it is configured such to address the vehicular approach from the north-west and the pedestrian approach from the south-east. A common foyer allows for dispersal into the different parts of the school. The class rooms are cross ventilated by the stair tower which inevitably rises up as a physical marker in the vast open. The top lit, multi-use atrium serves for large gatherings during winters and permits ample light. Large south-facing windows capture sunlight and keep the building warm during winters.

Another interesting design feature is the pier wall that has been developed as a single wall instead of the earth quake prone double wall. The building methodology introduced here is unique in its intention. It is not only inexpensive but also encourages change in how people build there. The signature pier wall is lighter and much stronger than the traditional 18” stone wall. Insulation is also taken care of by the cavity that is created between piers. Furthermore, the use of indigenous stone adds a local flavour, integrating the building with the landscape. This here is a classic case of an element being a symbol of changing building trends.

The context is imperative to the design of Aga Khan Gakuch. From the outside, the Architecture doesn’t try to overpower the picturesque landscape but rather sits in harmony. The landscape design takes clues from the existing backdrop, with only features to enhance what is naturally present. It becomes an emblem of how scenic sites are to be dealt with. These landscaped areas are used by the students for studying and playing, alike, a gathering zone that pushes inter-mingling.

In summation, the design is an effort to humanize the concept of development in an area which has had reservations about the subject. It attempts to address the needs of the students by providing a stimulating environment for academic and personal growth. It is intended to be a symbol of progression in an aloof locality. Users actively engage with the architecture and understand its role of coexisting with the environment. After all, in the words of Frank Chimero, people ignore design that ignores people.